Wouldn’t it be

nice if...more DVDs came with a choice of subtitles?

You may say – but

look! DVDs usually already come with a choice of subtitles!! Indeed as I write,

I have in front of me a copy of a Region 2 Special Collector’s Edition of Chinatown that offers subtitles in

English, Danish, Dutch, French, Finnish, German, Italian, Norwegian, Spanish

and Swedish as well as English subtitles for the hearing impaired. An

embarrassment of subtitling riches. Yes indeed. But this is not quite what I

mean.

I mean subtitles

which are addressed, not to different

audiences (French-speaking vs. German-speaking; hearing vs. Deaf, etc.), but to

the same audience who might simply

wish for different experiences of the film.

This is something

that DVD should be an ideal format for. And yes, there are many comedy films

which feature special feature subtitle tracks of various sorts on DVD. (My

favourite is probably the Ultimate Definitive Final special edition of Monty Python and the Holy Grail (2002),

which includes in the (unbelievably) Special Features ‘NEW! Subtitles For

People Who Don’t Like The Film’ which are a remix of lines from Shakespeare’s Henry IV, Part 2.) But these are gag

tracks, détournements, rather than ‘translating’

subtitle tracks. In 2010 we saw

Jean-Luc Godard fulfil what was, apparently, a long-cherished dream by releasing Film Socialisme at Cannes with audience-unfriendly subtitles.

When the film was released on DVD in the US by Kino Lorber it came with more

conventional titles too – but the choice to watch Godard’s ‘Navajo English’

titles was still there.

Once viewers cop on

to the fact that one translator’s set of subtitles might not be the same as

another’s, they often turn out pretty intrigued. And a few, brave distributors

have taken up the challenge.

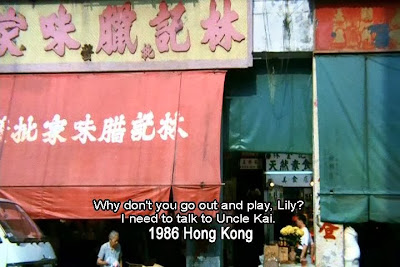

I’m thinking of

the subtitles offered on the 2007 Discotek Region 1 DVD release of Herman Yau’s

Ebola Syndrome (1996). This offers

both ‘crazy Hong Kong subtitles’[i]

and more recent conventional English subtitles:

I was, admittedly,

a little suspicious; some of the craziness in the ‘Hong Kong’ subtitles seemed

a little too good to be true, as with the following double entendre (the first title is from the conventional subtitles and the second from the 'crazy Hong Kong subtitles'):[ii]

But both sets of

subtitles can be used to watch and follow the film.

Ebola Syndrome is not the only Hong Kong

film to offer this feature on DVD. Wilson Yip’s Bio Zombie (1998, released on Region 1 DVD by Tokyo Shock in 2000)

also offers a choice of English subtitles (though it does not make a feature of

this on the cover of the DVD). Apart from the Cantonese original dialogue and

the English dub, viewers can choose Cantonese dialogue with English, or with ‘Engrish’

subtitles:

The Engrish

subtitles are the original subtitles for an earlier, Mei Ah DVD release. These

two subtitle tracks are entertainingly different, as we can see if we look at a

short sequence from one scene where the two anti-heroes properly launch their

careers as zombie killers. Here are the conventional English subtitles:

The same scene

with ‘Engrish’ subtitles goes as follows:

In some cases, it

is impossible to tell from the Engrish subtitles what the intended meaning of

the dialogue is, for instance, in this remark (the ‘correct’ subtitle is the

first one):

Cantonese speakers

who know the film are welcome to write in and explain how both these

translations can somehow be of the same Cantonese line of dialogue. In some

cases, the subtitles actually achieve the feat of saying the opposite to each other:

Nevertheless,

viewers of the Mei Ah DVD with only the ‘Engrish’ subtitles seem to be pretty

philosophical (see here and here), counting the DVD release’s low

price as a trade-off for the rather exotic translation.

Another example of

‘alternative’ subtitles, which I have commented on before, is the 2003

Criterion Collection edition of Kurosawa’s Throne

of Blood, which was published with two sets of subtitles by named

subtitlers: Linda Hoaglund and Donald Richie.

The two subtitlers

also contribute short pieces about their approach to subtitling in the sleeve

notes to the DVD. Hoaglund’s subtitles aim to achieve a slightly archaizing

register; Richie’s are intended to be fluent and easily readable. Their

subtitles are distinguished by different fonts:

A last, and very

pleasing, example of customer choice is the 2005 Region 1 Animeigo release of Incident at Blood Pass, also known as Machibuse, which offers ‘Japanese with

full subtitles’ and ‘Japanese with limited subtitles’:

I got very excited

about this; I thought that perhaps the ‘limited’ subtitles were ordinary dialogue

subtitles and the ‘full’ subtitles were the ones which included headnotes for

culturally specific concepts, explanations etc. In fact, on enquiry to Animeigo,

the ‘limited subtitles’ turned out to be the headnotes only, plus titles for

in-vision verbal material, without any dialogue titles:

The ‘full’

subtitles included both:

In a helpful

email, the company told me they included this feature as a response to customer

feedback; they have many viewers with enough Japanese to enjoy listening to the

dialogue, but not necessarily enough Japanese to read Japanese script in inserts and

captions easily, or catch cultural references. Apparently this is now a regular

feature on Animeigo releases.

But, readers may

say, these are really marginal examples, from a few films, most of them aimed

at a pretty niche audience. Are they really relevant?

Yes, I think so,

for several reasons:

1)

Providing a choice of subtitles

underlines the fact that all translation is based on choice and interpretation, and therefore good-quality screen translation cannot be taken for

granted.

2)

It helps to remind viewers that

the quality of the subtitles has a direct impact on the viewing experience. Many

DVDs seem ‘thrown together’ with

little thought to the quality of the text, much less the usability of menu

design or, perish the thought, the appropriateness of the translation choices.

Thinking about subtitle choice could be part of an overall awareness of the

importance of DVD design (and yes, I’m aware that DVD sales slipped nearly 20%

in 2012 on the year before – nevertheless, I have faith. Like books, I think

that just because they’re not the only game in town doesn’t mean they

are about to disappear).

3)

Naming the subtitler, as with

naming any translator of a text, is good practice, as Chris Durban has repeatedly argued.

Good quality should be appropriately rewarded.

4)

Seeing translation prominently

featured in the options and extras of DVDs helps people to be aware how

indispensable translators are in the making and distribution of film.

5)

Subtitles are a potential site

for play and 'added value' entertainment; in this sense, the more craptastic, the better.

Is it ‘the way of

the future’? Probably not; we know from tired experience that distributors and DVD publishers are pretty cavalier about subtitles. But there are a number

of films which are crying out for a nice premium rerelease with added

translationy goodness: think Mädchen in Uniform – wouldn’t it be great to be able to access the original French subtitles

by Colette, or the scattered English subtitles – all 124 of them – which

appeared on the first translated print screened in the UK in 1932? Or what

about Bekmambetov’s Day Watch, whose

UK and US releases disappointed viewers who had been looking forward to the

funky theatrical subtitles? Where subtitles have generated controversy and

complaint, DVD would offer a nice opportunity to compare and contrast – for

instance, the much-complained-about version of Les 400 coups rereleased by the BFI in 2010 which had to be resubtitled when audiences pointed out that quite a lot of the

dialogue in the film never made it as far as the subtitles.

In the meantime,

I’d settle for companies providing a choice between subtitles for the

hearing impaired, and subtitles for the hearing. Too many companies cut corners

like this. You know who you are. (Please feel free to name and

shame offenders in the comments.)

Carol O’Sullivan

(c) 2013

UPDATE 2014: Delighted to say that there is a French translation of this post on Les Piles Intérmediaires under the title 'À quand des "sous-titres pour ceux qui aiment vraiment le film"?'.

[i] ‘Hong Kong’ subtitling is a recognized phenomenon in which

subtitles are produced by non-native English speakers and as a result feature

startling, and sometimes hilarious, translation solutions. For more on this see

David Bordwell, Planet Hong Kong: Popular

Cinema and the Art of Entertainment. Madison, WI: Irvington Way Institute

Press, 2011, p.78

[ii] For interested French speakers, the French subtitle for the Metropolitan

DVD release (2006) reads “Li, va jouer dehors, / je

dois parler avec Kai” (titles by Jean-Marc Bertrix).